Menora v. Illinois High School Association

| Menora v. Illinois High School Association | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit |

| Full case name | Moshe Menora et al. v. Illinois High School Association |

| Decided | June 30, 1982 |

| Citation | 683 F.2d. 1030 |

| Case history | |

| Prior actions | judgment for plaintiffs, 527 F. Supp. 637 (N.D. Ill. 1981) |

| Subsequent actions | rehearing, rehearing en banc denied, 683 F.2d 1030 (7th Cir. 1982)

certiorari denied, 103 S.Ct. 801 (1983) settlement reached, 1983 |

| Court membership | |

| Judges sitting | |

| Case opinions | |

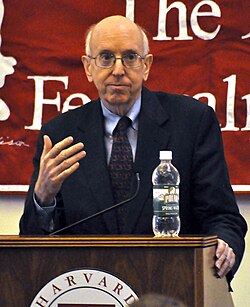

| Majority | Posner, joined by Eschbach |

| Dissent | Cudahy |

Menora v. Illinois High School Association, 683 F.2d 1030 (7th Cir. 1982), is a case heard by the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit centered on two Jewish schools looking to play in an interscholastic basketball tournament run by the Illinois High School Association (IHSA). The IHSA barred the schools from playing because the players refused to take off their kippot (religious head-coverings), which violated a rule against players wearing headgear on the court. The schools sued the IHSA in 1981, arguing that their First Amendment right of freedom of religion had been violated; the IHSA responded that the safety concern was reasonable because a kippah could fall off during play, causing injury. The Seventh Circuit held that no conflict would exist between the two parties if the schools designed a head-covering that was not a safety risk; the case was settled on remand to the district court in June 1983.

Under the Supreme Court's ruling in Sherbert v. Verner (1963), government restriction of religion has to be justified by a compelling interest that outweighed the loss of religious freedom, and the restriction still has to preserve as much religious freedom as possible. Applying the Sherbert test, the District Court for the Northern District of Illinois decided the case for the schools; the IHSA could not provide any evidence that kippot had ever caused an injury. Shadur found that the ISHA did not have a compelling interest compared to the religious freedoms of the students.

The Seventh Circuit vacated the district court's ruling, applying the "false conflict" method to the case – in this approach, the court rigorously defines the interests of the two parties, and in doing so, may find that little to no conflict exists. The Court reasoned that if the schools could design a head-covering that met the IHSA's safety concerns, which the Court felt were reasonable, the conflict would be resolved. The dissent argued that the district court had correctly interpreted Sherbert and that the ruling should not have put the burden of resolving the conflict on the schools. A settlement was reached in June 1983, allowing kippot to be worn if secured with contour clips.

Legal scholars criticized the Seventh Circuit's false conflict approach as unsupported by precedent, writing that if the Sherbert test were properly applied, the Court would have put the burden on the IHSA to uphold safety without infringing on religious freedom, not the schools. American Jewry largely took it as a victory that the students were eventually allowed to play with kippot on. The Supreme Court's later ruling in Employment Division v. Smith (1990) limited the reach of the Sherbert test, possibly making it inapplicable to cases like Menora.

Background

[edit]Case

[edit]According to halakha, the main body of Jewish law, Jewish men are required to wear a head-covering when they pray or when they say a blessing over food. The head-covering commonly worn by Jewish men is known as a kippah (pl. kippot), but no law requires that the head-covering be a kippah. Throughout the early 20th century, religiously observant Jewish men in America usually only wore a kippah when the law required, but by the 1950s and '60s, the kippah had become a more widespread religious symbol, and they began to wear the distinctive head-coverings whenever possible, including in public.[1] The shift has been attributed to multiple causes, but the change itself signaled that Jews were adopting a more religious lifestyle and doing so openly, combining their Jewish and American identities. Some Orthodox Jewish schools shifted with the culture, requiring as an interpretation of halakha that students wear kippot as often as possible.[2]

In February 1981, two rival Orthodox Jewish schools in Chicagoland, Ida Crown Jewish Academy and Yeshiva High School,[a] were slated to compete in the Illinois high school men's basketball tournament; it would be the Yeshiva's first time competing in the tournament, having only been a conference member for a few years.[5] The tournament was governed by the Illinois High School Association (IHSA), a private organization that regulates sporting competition between all high schools in the U.S. state of Illinois. Nearly all high schools in the state, whether public or private, are members.[6] For safety reasons, IHSA rules prohibit headgear from being worn on the court with a few limited exceptions.[7] Many other state leagues had the same rule, since it was derived from a model code published by the National Federation of State High School Associations.[8] However, the students had been wearing kippot while playing basketball for years, fastening them with bobby pins[9] – the two schools played a cumulative total of 1,300 basketball games in the IHSA, all with kippot.[10]

As the tournament approached, the IHSA held (supported by an NFHS interpretation) that kippot were barred by the rules and that players could not wear them, despite lobbying from people associated with the Ida Crown and the Yeshiva that kippot were entirely safe; the Yeshiva's first opponent, the top-seeded Harvard High School, also had no issue with students competing with kippot. Unwilling to participate under these conditions, students from the two Jewish schools, along with their parents and the schools themselves,[11] sued the IHSA in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, claiming that their freedom of religion was being violated.[12]

Free Exercise Clause

[edit].jpg/500px-Warren_Court_(1962_-_1965).jpg)

The Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees that "Congress shall make no law ... prohibiting the free exercise [of religion]". In Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940), the Supreme Court ruled that the text also applies to state governments under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.[13] For much of the Supreme Court's history, it held that the government's interests justified restricting the freedom of religion, but that a law restricting the freedom of religion could still be struck down if it also violated some other constitutional right, like freedom of speech.[14]

That changed with Sherbert v. Verner (1963), a Supreme Court case about a woman who was denied unemployment benefits because, not willing to work on Saturdays as a Seventh-Day Adventist, she refused some offers of work. The Court ruled that the state had no compelling reason to force the woman to choose between her freedom of religion and public benefits; in the process, it laid out a balancing test based only on the Free Exercise Clause for the first time. To justify impeding the freedom of religion, the government would have to show that it had a compelling reason to do so, that the law it was enforcing was concretely connected to that reason, and that there was no less intrusive way to achieve its goals.[15]

Sherbert was a significant expansion of the Free Exercise Clause's scope and power, followed by several more decisions expanding religious liberty. In Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972), the Court held that "only [government] interests of the highest order ... can over-balance legitimate claims to the free exercise of religion", and applied the Free Exercise Clause to government-run schools. In Thomas v. Review Board (1981), the Court reiterated the balancing test created in Sherbert and held that a person's interpretation of their own religious obligations is protected under the Free Exercise Clause even if that interpretation is not widely shared by other adherents to the same religion.[16]

However, the Sherbert test leaves open several questions, like whether and how rigorously to question the sincerity of a plaintiff's beliefs, or whether factual evidence should be required to demonstrate that a law actually succeeds at furthering the government's interest. Lower courts split on how to handle those questions, creating an inconsistent overall approach.[17] Some people, interested in alternatives to the Sherbert test, argued for adapting a method developed by Professor Brainerd Currie for other areas of law, intended to resolve conflicts of laws. Called the "false conflict" approach, Currie advocated for trying to resolve conflicts of laws by rigorously defining the purposes and interests behind each law; in some cases, Currie argued, laying out the competing interests might reveal that there actually is no conflict between them, or that an approach can be found that easily satisfies both. Some have argued for extending this approach to Free Exercise cases.[18]

Court proceedings

[edit]District court

[edit]

The students, represented by attorneys for the American Jewish Congress,[19] asked for an injunction and declaratory judgment allowing them to compete with their kippot on. They contended that wearing a kippah was required by their faith, a position the IHSA did not dispute,[20] and argued that the IHSA's ruling improperly forced them to compromise either their religious adherence or tournament participation. They also disputed the effectiveness of the ruling, arguing that wearing kippot did not pose safety risks and that the IHSA's ruling was therefore both unnecessary and discriminatory. The IHSA defended its holding as a reasonable safety measure, arguing that a player could slip on a kippah that fell off another player's head.[21] They also argued that, as a private organization, they should not be bound by First Amendment restrictions.[22]

The case was first heard by Judge Milton Shadur in the District Court for Northern District of Illinois, who quickly granted a temporary injunction allowing the students to compete in the upcoming tournament on February 23. The judge promised both sides that he would hold a speedy hearing if the teams advanced in the playoffs, but both teams were knocked out in the first round: the Yeshiva was routed by Harvard High School, 99–54, and Ida Crown lost to St. Gregory the Great High School, 79–51.[23]

Following the injunction, Rabbi Oscar Z. Fasman of the Yeshiva lobbied the IHSA to add a permanent exception to their rule, citing the religious significance of kippot to Jews. This was unsuccessful, and the IHSA in fact strengthened their rule by removing some previously available exceptions. The IHSA also asked Shadur to recuse himself, citing his Judaism and a previous connection to the American Jewish Congress; he refused, viewing both the request and the IHSA's rule change negatively.[24]

In November 1981, the district court ruled in favor of the students, holding that the IHSA violated their First Amendment rights. Shadur ruled that the IHSA was bound by the First Amendment despite its status as a private organization; the majority of its members were public schools and no other statewide basketball league existed in Illinois.[25] He stressed the religious importance of the kippah to the players, writing that their beliefs "stem from the ancient Talmud".[26] Shadur concluded that the IHSA was restricting the student's freedom of religion by forcing them to choose between their religion and playing basketball; in applying the Sherbert test, he found that the safety risks posed by kippot were "totally speculative", ruling that the IHSA therefore did not have a compelling state interest in regulating them.[27] The IHSA appealed the decision to the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit.[19]

Appeals court

[edit]

In June 1982, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals vacated the district court's judgement in a 2–1 decision,[28] holding that the Court did not need to apply the Sherbert test because no conflict actually existed between the parties. Judge Richard Posner, writing for the majority, took the false conflict approach and first defined the interests of the parties: the IHSA's interest was in maximizing player safety, and the students' interest, he said, was the opportunity to play basketball in accordance with their religious beliefs. He concluded that the IHSA's interest in safety was reasonable and that, while the players' religious interests were also valid, they were only required by their religion to wear a head-covering; choosing a kippah, he said, was a matter of custom.[29]

Posner – reasoning that the court did not need to decide which interest was more important if an approach could be found that satisfied both parties – held that the students could satisfy the IHSA's safety interest and maintain their own religious beliefs by designing a head-covering with less risk of falling off of their heads during play. Without that step, he ruled, the plaintiffs had not actually proven that the IHSA was infringing their First Amendment rights. He remarked for the Court that "we put the burden of proposing an alternative, more secure method of covering the head on the plaintiffs rather than on the defendants because the plaintiffs know so much about Jewish law"; however, he warned, if the students successfully designed a more secure head-covering and the IHSA still refused to budge, the IHSA would be standing on "constitutional quicksand".[30]

Judge Richard Dickson Cudahy wrote a solo dissent that mostly agreed with the district court's analysis, underlining the harm done to students by not allowing them to practice their religion while playing basketball, effectively not allowing them to play at all. By forcing the students to make that choice, Cudahy wrote, "[the] IHSA's no-headwear rule has imposed a significant, albeit indirect, burden on religion".[31] Cudahy criticized the majority opinion's false-conflict analysis, arguing that a conflict did exist because the IHSA refused to compromise on their headgear ban, regardless of how securely fastened the headgear was. He disagreed that the IHSA's safety concerns had merit compared to the harm to the students' religious freedoms, citing the district court analysis that the safety risks were only speculative. In that light, Cudahy wrote, the majority should have applied the Sherbert test and ordered the IHSA to revise its rules, instead of putting the burden on the students to design a new head-covering.[32]

The Seventh Circuit remanded the case back to the district court.[33] In January 1983, the Supreme Court voted against hearing the case, with Justices Harry Blackmun and Thurgood Marshall dissenting.[34]

Settlement in the district court

[edit]Posner's decision was a blow to the schools, but not a resounding victory for the IHSA, either; the ruling forced the IHSA to reach some kind of agreement with the schools, so they could not keep a complete head-covering ban. Lawyers for the schools, looking to avoid a situation where students might have to wear an absurd head-covering, told the IHSA that "according to our clients, Jewish law mandates the covering of the head for purposes of showing respect to God. It is our clients' sincerely held religious belief that requiring the students to wear bizarre headwear would violate Jewish law." No such provision exists in halakha, but by that time, the kippah had become a symbol of Orthodox Judaism to the wider American public, one that communicated continuous observance and identity, and Orthodox leaders felt that an unfamiliar head-covering would not carry that same weight.[35]

Ida Crown and the Yeshiva hired a scientist to come up with a kippah that could be worn safely. They tested kippot with different materials, different conditions of the scalp, and different fasteners. They found that contour clips kept kippot in place much more effectively than bobby pins, and using contour clips would not be much of a change, as they were already somewhat in use. The IHSA agreed to allow kippot secured by contour clips, and in June 1983, Judge Shadur accepted the terms of the settlement, ending the case.[35]

Reaction, analysis, and impact

[edit]Legal reaction and analysis

[edit]Legal scholars criticized Posner's false-conflict approach, instead holding up Shadur and Cudahy's approach based on the Sherbert balancing test as a better interpretation of case law. Judith Mills, writing in the Wisconsin Law Review, and Dale E. Carpenter,[b] writing in the Indiana Law Journal, highlighted the similarities in the facts of the two cases: both involved a religious person being forced to choose between receiving a government benefit available to the public or freely exercising their religion. If the facts of the cases were similar, Mills argued, the Seventh Circuit should have applied the test developed by the Supreme Court for those facts.[36]

Mills and Carpenter both argued that Posner's approach incorrectly assessed the harm done to the students in terms of their participation in basketball, and not the burden on freedom of religion that made them unable to play. By ignoring the harm to the students' freedom of religion and giving more weight to the IHSA's safety claim, they wrote, the Court reached the wrong answer. They also argued that the Court made a mistake in putting the burden on the students, rather than the IHSA, to resolve the conflict; correctly applying the Sherbert test, they said, would force the IHSA to uphold safety in a way that burdens freedom of religion as little as possible.[37] Carpenter – along with Kurt Feuerschwenger in the DePaul Law Review – also argued that the false-conflict approach could not even apply to this case because the IHSA had refused to make an exception for the students no matter how the kippot were attached, forcing a conflict.[38]

Feuerschwenger acknowledged that the Sherbert test was difficult to apply, relying on a subjective weighing of religious and state interests. However, he argued that even in trying to avoid the Sherbert test, the Seventh Circuit still weighed the competing interests in its decision. He wrote that Posner, by upholding the IHSA's safety claim as not completely unreasonable and making the students' claims primarily about basketball, still engaged in comparing the two interests, failing to avoid the complexity and confusion that the Sherbert balancing test had been criticized for.[39] Posner's test, he argued, also made it too easy for the state to justify its laws, requiring only a "rational relation" and only considering the law's purpose, rather than its actual reach.[10] Feuerschwenger instead proposed applying the strict scrutiny test used for the Equal Protection Clause, which only looks at the merits of the legislation rather than weighing it against the religious claim. He also suggested making the government prove that the legislation it is defending accomplishes its stated goals.[40]

Feuerschwenger and Mills also criticized the Court for seemingly giving less protection to the students' beliefs by concluding that, because halakha only requires a head-covering, the students have on religious interest in wearing kippot specifically; they argued that under the Supreme Court's ruling in Thomas v. Review Board, a sincerely held belief should have First Amendment protection regardless of whether it is a part of established doctrine or a custom.[41]

Other reactions and impact

[edit]For American Jewry at large, the eventual settlement of the case in their favor was hailed as a victory for their freedom of religion; the American Jewish Congress declared victory and earned praise for its legal advocacy. For Orthodox Jews, the settlement affirmed the central role of the kippah as a symbol of their public-facing identity and observance. Zev Eleff, in his book Authentically Orthodox: A Tradition-Bound Faith in American Life, related an anecdote from fall of 1983, when the Yeshiva's varsity basketball team was beginning preseason practice. One student – only vaguely aware of the Menora case – accidentally dropped his small kippah and, in the interest of efficiency, kicked it under the bleachers. Surprisingly for him, the coach loudly ordered him to stop playing and pick it back up, musing, "if you only knew the trouble we went through to make sure you could play basketball with your head covered".[42]

The Supreme Court weakened the Sherbert test in 1990, ruling in Employment Division v. Smith that the test does not apply to generally applicable laws that do not single out religious conduct.[43] Scott Idleman wrote in the Marquette Sports Law Review that Smith would most likely have undercut Sherbert's applicability to the case; however, he also argued that since public headwear is expressive conduct, the plaintiffs could pair the freedoms of religion and speech to make a combined claim under pre-Sherbert case law. If that failed, the students would have had to show that the headgear ban failed rational basis review, which Idleman wrote would be "a difficult task indeed".[44] As of 2013[update], Menora v. Illinois High School Association remains the only case heard in a federal appellate court on the topic of religious headwear in schools.[45]

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Yeshiva High School was renamed "Fasman Yeshiva High School" in 1981 after Rabbi Oscar Z. Fasman; it is a division of Hebrew Theological College in Skokie, Illinois,[3] the named plaintiff along with Ida Crown.[4] Chicago Tribune 1981 and Eleff 2020 both refer to the school as "Yeshiva High School"; this article retains that usage for consistency throughout.

- ^ Not to be confused with Dale Carpenter.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Eleff 2020, PDF pp. 79–81, 97; Feuerschwenger 1983, pp. 446, fn. 80.

- ^ Eleff 2020, PDF pp. 82–83.

- ^ Hebrew Theological College.

- ^ Menora at 1030.

- ^ Eleff 2020, PDF pp. 79, 90.

- ^ Feuerschwenger 1983, p. 444.

- ^ Eleff 2020, PDF pp. 90–91; Nemani 2013, p. 67.

- ^ Hensley 2024, p. 36.

- ^ Carpenter 1987–1988, p. 610.

- ^ a b Feuerschwenger 1983, p. 450.

- ^ Evansville Press 1981; Chicago Tribune 1981.

- ^ Eleff 2020, PDF pp. 90–91.

- ^ Mills 1983, pp. 1489, fn. 16, quoting U.S. Const. amend. I.; Cantwell.

- ^ Feuerschwenger 1983, fn. 22.

- ^ Feuerschwenger 1983, p. 437–438, fn. 22; Mills 1983, pp. 1489–1490.

- ^ Feuerschwenger 1983, pp. 438–439; Mills 1983, pp. 1490–1491. Quoting Yoder at 215.

- ^ Feuerschwenger 1983, pp. 441–442.

- ^ Feuerschwenger 1983, p. 443; Carpenter 1987–1988, fn. 65.

- ^ a b Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle 1982.

- ^ Eleff 2020, PDF pp. 84, 91.

- ^ Eleff 2020, PDF p. 92; Feuerschwenger 1983, pp. 444–445.

- ^ Nemani 2013, p. 67; Eleff 2020, PDF p. 95.

- ^ Eleff 2020, PDF pp. 92–93; Evansville Press 1981.

- ^ Eleff 2020, PDF pp. 93–95; Chicago Tribune 1981.

- ^ Nemani 2013, p. 67; Eleff 2020, PDF p. 95.

- ^ Eleff 2020, PDF p. 95.

- ^ Eleff 2020, PDF p. 95; Feuerschwenger 1983, p. 445.

- ^ Mills 1983, p. 1487; Eleff 2020, PDF p. 96.

- ^ Feuerschwenger 1983, pp. 445–446; Carpenter 1987–1988, p. 610.

- ^ Feuerschwenger 1983, pp. 445–446; Carpenter 1987–1988, p. 610. Quoting Menora at 1035.

- ^ Mills 1983, pp. 1492–1493. Quoting Menora at 1037 (Cudahy, J., dissenting).

- ^ Mills 1983, pp. 1496–1497, 1500, fn. 7.

- ^ Mills 1983, fn. 76.

- ^ The Dispatch 1983.

- ^ a b Eleff 2020, PDF p. 97.

- ^ Mills 1983, p. 1493; Carpenter 1987–1988, p. 611.

- ^ Carpenter 1987–1988, pp. 611–612; Mills 1983, pp. 1494, 1499.

- ^ Carpenter 1987–1988, p. 611; Feuerschwenger 1983, pp. 451–452.

- ^ Feuerschwenger 1983, pp. 446–447.

- ^ Feuerschwenger 1983, pp. 453–454.

- ^ Feuerschwenger 1983, pp. 448–449; Mills 1983, pp. 1495–1496.

- ^ Eleff 2020, PDF pp. 97–98.

- ^ Idleman 2001, pp. 306–307.

- ^ Idleman 2001, pp. 334–335.

- ^ Nemani 2013, fn. 101.

Academic sources

[edit]- Feuerschwenger, Kurt H. (1983). "Inconsistent judicial protection of religious conduct: The Seventh Circuit contributes to the confusion in Menora v. Illinois State High School Association". DePaul Law Review. 32 (2): 433–456. Retrieved November 9, 2024.

- Mills, Judith M. (1983). "Menora v. Illinois High School Association: Basketball players' Free Exercise rights compromised – technical foul". Wisconsin Law Review. 1983 (6): 1487–1504. Retrieved November 9, 2024.

- Carpenter, Dale E. (1987–1988). "Free Exercise and dress codes: Toward more consistent protection of a fundamental right". Indiana Law Journal. 63 (3): 601–622. Retrieved May 14, 2025.

- Idleman, Scott C. (2001). "Religious freedom and the interscholastic athlete". Marquette Sports Law Review. 12 (1): 295–346. Retrieved November 9, 2024.

- Nemani, Priti (2013). "Piercing politics: Religious garb and secularism in public schools". Asian American Law Journal. 30 (1): 53–82. Retrieved November 9, 2024.

- Eleff, Zev (2020). Authentically Orthodox: A Tradition-Bound Faith in American Life. Wayne State University Press.

- Hensley, Matthew (2024). Competitive balance solutions in interscholastic athletics in Illinois: A historical-interpretive analysis (Ed.D. thesis). University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved July 19, 2025.

News sources

[edit]- "Yarmulkes may be worn in Illinois tournament". Evansville Press. United Press International. February 24, 1981. Retrieved November 9, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- "Rabbi hits IHSA on yarmulke rule". Chicago Tribune. February 28, 1981 – via newspapers.com.

- "AJCongress cries foul". Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. April 30, 1982. Retrieved November 9, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- Unger, Rudolph (July 29, 1982). "Sport rule becomes a religious issue". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 9, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- "High court stays out of dispute over skull caps". The Dispatch. January 17, 1983. Retrieved November 9, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- "Slam-dunking with yarmulkes". Los Angeles Times. July 10, 1983 – via newspapers.com.

Legal sources

[edit]- Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296 (1940).

- Sherbert v. Verner, 347 U.S. 398 (1963).

- Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972).

- Thomas v. Review Board of the Indiana Employment Security Division, 450 U.S. 707 (1981).

- Menora v. Illinois High School Association, 527 F. Supp. 637 (N.D. Ill. 1981).

- Menora v. Illinois High School Association, 683 F.2d 1030 (7th Cir. 1982).

- Employment Division v. Smith, 494 U.S. 872 (1990).

Other sources

[edit]- "History". Hebrew Theological College. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]Source texts

[edit]- Text of Menora v. Illinois High School Association, 527 F. Supp. 637 (N.D. Ill. 1981) is available from: Justia

- Text of Menora v. Illinois High School Association, 683 F.2d 1030 (7th Cir. 1982) is available from: Justia

Related cases

[edit]- Close-It Enterprises v. Weinberger, 407 N.Y.S.2d 587 (1978)

- Goldman v. Weinberger, 475 U.S. 503 (1986)

- Iacono v. Croom, No. 5:10-CV-416-H (E.D. N.C. Oct. 8, 2010) (granting temporary restraining order)

Academic texts

[edit]- Zimmer, Eric (1992). "Men's headcoverings: the metamorphosis of this practice". In Schachter, Jacob J. (ed.). Reverence, Righteousness, and Rahamanut: Essays in Memory of Rabbi Dr. Leo Jung. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-87-668591-4.

- Domnarski, William (2016). Richard Posner. Oxford University Press. pp. 59–95. ISBN 978-0-19-933231-1.